Albers Brothers Milling Co

Multnomah Co. | Oregon | USA

Watersource: Steam & electricity.

Albers Brothers Milling Co

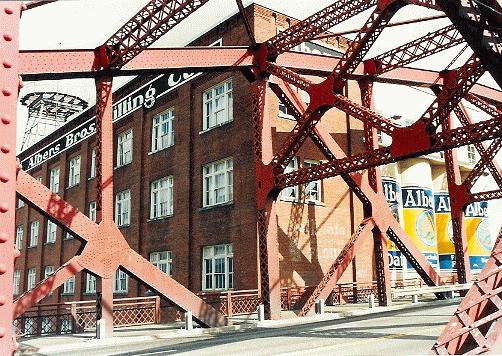

In Portland on the west side of the Willamette River at the west end of the Broadway Bridge/Sh 99W on Front Street, just north of Union Station.

The original mill was downtown on Front St. near Main and Salmon Sts. The opening of the new mill, above, in 1911 just north of the west end of the Broadway Bridge/Or 99W, saw the wheat industry in Oregon at the peak of a boom that began in 1885; when, the railroads arrival brought immeasurable amount of wheat to the Portland shipping docks from Central and Eastern Oregon growing slopes.

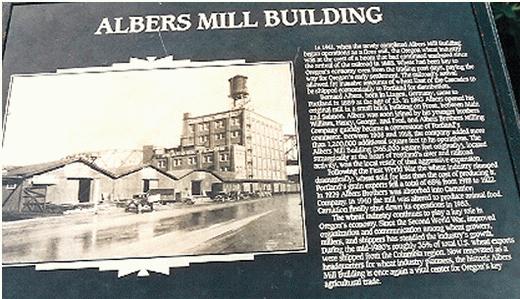

From the Portland location, the wheat could be milled and shipped out to virtually any destination in the world. One of the brands of flour milled was called Peacock Flour. The photo above is of a placque of the mill and a description of its history. In 1893, Bernard Albers of Lingen, Germany, at age 29, built his first mill on Front St. near Main and Salmon Sts. just north of the present west end of the Hawthorne Bridge over the Willamette River. He was soon joined by his younger brothers William, Henry, George, and Frank. Between 1908 and 1918 saw expansion of the 360,000 sq. ft. new mill to eventually include over 1 million sq.ft. of mill operation.

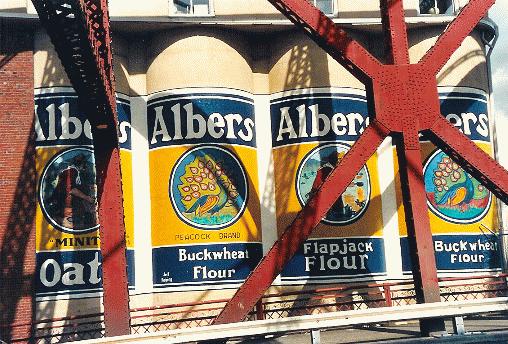

Then photo above shows the 1893 plant with later added storage silos decorated with Albers Products. Wheat prices fell badly, some 65%, following WWI. Growing wheat was almost cost inefficient. The Carnation Company assumed control of operations at Albers in 1929, and by the year 1940, production had been switched to animal feeds. This last feed operation ceased completely in 1983, a run of about 43 years, not bad considering its location in a large city.

The wheat indusrty had a slight revival in the 1980's as 35% of the wheat exports from the United States originated in the Columbia Basin area. The renovated mill is now the home to agencies involved in planning for the wheat industry of the future. So! the mill is not yet dead. It still has a hand in determining the wheat industry's future in the Northwest.